The Necessary and Sufficient Requirements for the Holy Grail of Supply Chain Management

Every importer, manufacturer, and distributor is chasing the same illusion: that one day they’ll finally have a supply chain that “just works.” They’ll know where everything is, what it costs, when it will arrive, and what to do when it doesn’t.

What they really want is reliability — not in the narrow sense of on-time delivery, but in the broader sense of control that endures in the face of complexity.

That ideal — the holy grail of supply-chain management — is a system that is self-aware, self-correcting, and fully synchronized with the physical and financial realities of the enterprise.

It sounds mythical, but it isn’t. We can define it precisely, and we can describe exactly what’s necessary and sufficient to achieve it.

Defining the Holy Grail

The holy grail is achieved when an enterprise can continuously, accurately, and autonomously manage the movement, cost, and compliance of its products from origin to destination — in alignment with both physical reality and corporate intent.

Three distinct worlds must be synchronized:

- The Physical World – where goods actually move.

- The Digital World – where those movements are modeled, tracked, and predicted.

- The Corporate World – where planning, finance, and customer promises live.

When those three worlds act as one, the supply chain stops being an opaque series of hand-offs and becomes a living system that understands itself.

The Principle of Necessity and Sufficiency

Many frameworks describe what “good” looks like — visibility, integration, collaboration — but very few answer the harder question:

What is both necessary and sufficient for control?

That test eliminates the noise. If something can be removed without destroying systemic reliability, it isn’t necessary. If something is required but not enough on its own, it isn’t sufficient.

After stripping the problem to its essentials, only six conditions remain that satisfy both criteria. Remove any one of them and the system collapses. Add anything else and you gain convenience, not capability.

Condition 1: Persistent Control Objects

All control starts with representation. You cannot manage what you cannot describe, and you cannot describe it with spreadsheets.

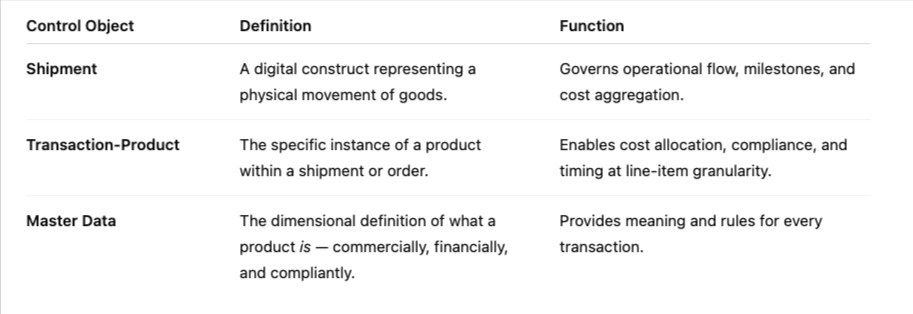

Every resilient supply-chain system requires three — and only three — persistent digital control objects:

The shipment defines movement, the transaction-product defines content, and master data defines context. When these three objects exist and remain relationally intact across all systems, the organization can understand any event, any cost, any delay, anywhere in its network.

Without them, the enterprise is blind — every other technology becomes noise layered on confusion.

Condition 2: A Causal Chain of Events

Visibility is not control. Control requires causality — an understanding of why something happens, not just that it did.

Every shipment must be modeled as a causal chain composed of:

- Nodes – physical locations or states (factory, port, terminal, warehouse).

- Vectors – movements between those nodes (dray, sail, rail, delivery).

Each node and vector carries temporal attributes — planned, estimated, actual — and business rules about sequence and dependency.

This causal chain allows the system to infer:

- What has occurred,

- What must occur next, and

- When downstream events will be affected by upstream changes.

The Dual Reality of Shipments

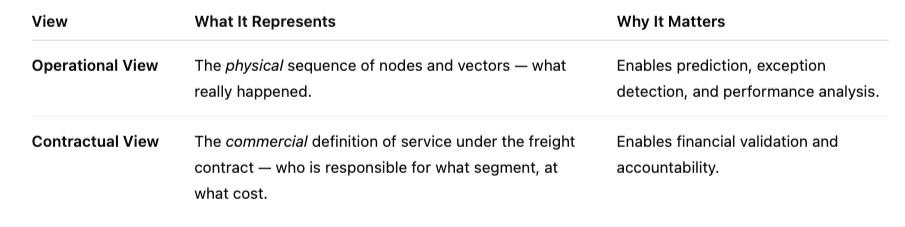

In international trade, a shipment lives in two overlapping realities:

Domestic moves rarely require both; a truckload from Toronto to Chicago is both operationally and contractually identical. But in global logistics, these diverge. A single “port-to-door” contract can span multiple operational legs — ocean, rail, drayage, terminal handling — executed by different actors.

Only by maintaining both views in parallel can a system reconcile performance against obligation and cost against reality.

Condition 3: Continuous Data Reconciliation

Even the most elegant model decays the moment it stops being updated. Real supply chains are dynamic systems; they require constant sensory input.

A self-aware supply-chain platform must:

- Ingest operational data from carriers, forwarders, and brokers (EDI, API, IDP, IoT).

- Validate every event against the control objects it claims to describe.

- Resolve conflicts among sources based on trust hierarchies.

- Record a versioned history of what was known and when.

This continuous reconciliation is what keeps the digital model in lock-step with the physical world. Without it, data entropy takes over. A shipment’s “status” becomes an opinion instead of a fact, and all downstream automation fails.

Condition 4: Rules-Based Automation and Exception Management

A system that only reports exceptions isn’t intelligent; it’s needy.

True control emerges when the system knows how to act. Every control object must carry with it a set of conditional rules defining:

- Expected performance (e.g., ETA variance ≤ 2 days)

- Tolerances (e.g., demurrage risk < $500)

- Authorized responses (e.g., auto-notify customer, pre-pull container, re-forecast ship plan)

When reality deviates, the system executes those rules immediately — escalating only the exceptions that require judgment.

This is where “visibility” becomes autonomy.

It’s the difference between knowing a shipment is late and having the system update every dependent promise before anyone notices.

Condition 5: Governance and Accountability

This one is less glamorous but absolutely necessary. The previous four conditions create alignment; governance keeps it from drifting.

Governance isn’t about bureaucracy — it’s the mechanism that resists entropy. Without it:

- Master data slowly diverges from ERP truth.

- Rules become outdated as service networks change.

- Integrations break silently when partners alter formats.

- Exceptions pile up in unattended queues.

Everything still exists, but nothing stays true.

Governance provides ownership:

- Who validates new suppliers, products, and accounts.

- Who approves rule changes and automation thresholds.

- Who audits data integrity and integration health.

It’s the immune system of the digital supply chain — invisible until the day you need it.

Condition 6: Integration with the Corporate Environment

This is the most complex — and the most overlooked — requirement.

A supply-chain system can achieve perfect internal control and still fail the business if it isn’t synchronized with the rest of the enterprise. Operational truth only has value when it informs corporate decisions — and corporate decisions only succeed when they’re grounded in operational truth.

The Corporate Environment Defined

The “corporate environment” is not one system; it’s a federation of functions, each optimizing for a different objective:

Each operates on its own cadence — daily for sales, monthly for finance, quarterly for S&OP — and interprets the same shipment differently.

The integration layer’s job is to translate and synchronize these perspectives continuously.

The Three Planes of Integration

When these three planes operate together, the company moves from reactive firefighting to adaptive orchestration — an enterprise that senses and responds rather than plans and prays.

Why These Six and Only These Six

Everything else — predictive analytics, dashboards, AI — are derivatives of these six. They make the experience better; they don’t make it possible.

If you possess:

- Persistent control objects

- A dual-view causal chain

- Continuous reconciliation

- Rules-based automation

- Governance and accountability

- Integration with the corporate environment

…then you have a system that knows what’s happening, understands why, acts when it should, and keeps the business in sync with reality.

If any one of these is missing:

- You may have visibility but no control.

- You may have data but no truth.

- You may have automation but no intelligence.

- You may have planning but no reliability.

From Control to Reliability

The holy grail isn’t about technology; it’s about systemic reliability. Reliability is what happens when every movement, cost, and commitment across the enterprise is grounded in causal truth and continuously synchronized with intent.

At that point, the supply chain ceases to be an operational burden and becomes a strategic capability — a nervous system that senses, interprets, and responds faster than its competitors.

That’s the grail: Not magic.

Not AI.

Just a system that finally understands itself.

Closing Thought

In the end, the holy grail isn’t a future technology; it’s a present discipline. It’s a commitment to model the world as it truly operates — causally, dimensionally, and continuously. Do that, and the myth becomes mechanical: reliability by design.